Kernza® Perennial Grain

Kernza seedheads ripening under the Minnesota sky. The plant itself, called intermediate wheatgrass, is

distantly related to wheat. Photo by Amy Kumler

A revolutionary new grain called Kernza® is igniting a movement to feed the world while restoring damaged soils and protecting groundwater from nitrogen pollution. To accelerate the pace of change, in 2016 we brought to market the world’s first commercial Kernza product, a delicious beer called Long Root® Pale Ale. Now we’re offering Kernza pasta, infused with the nutty, buttery flavor of this remarkable grain.

Nutrition: Good for Soil, Good for Humans

Healthy soil filled with Kernza® roots and legume nodules at Sustain-A-Grain farm near Moundridge, central Kansas. The roots and nodules host millions of soil-restoring bacteria. Photo by Amy Kumler

Kernza® perennial grain contains more protein, dietary fiber and certain nutrients than common wheat varieties.

Annual grains like wheat, rice and corn currently occupy about 70% of the world’s farmland. In contrast to these annually planted varieties, Kernza is a perennial, remaining in place year after year. This allows it to develop a complex web of roots that nourish the microbiome of the topsoil. Meanwhile, those penetrating roots allow the plant to find underground water and nutrients that remain inaccessible to annuals. The result is a finished grain that’s both delicious and, when compared to annual wheat, a better source of fiber, plant-based protein, and essential amino acids. Kernza also contains higher levels of the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin, which have been associated with eye and cardiometabolic health, as well as higher antioxidant activity.

Stalks of Kernza grains and husks from threshed seed. Salina, Kansas. Photo by Amy Kumler

Sourcing: Raised in the Heartland

Harvesting Kernza samples at dawn before the sun begins to blister down. The Land Institute, Salina, Kansas. Photo by Amy Kumler

Our Kernza® comes from American farmers committed to regenerative agriculture.

Over millennia, the prairies of America’s Midwest formed some of the richest topsoil in the world. But after 150 years of industrial agriculture, that same soil now struggles to produce reliable crops without the addition of synthetic fertilizers. Meanwhile, family farmers find themselves on the frontlines of climate change. Floods, droughts, and unseasonable weather are becoming routine. Kernza offers farmers the chance to tackle both problems head-on.

As Josh Svaty of Free State Farms in Kansas puts it, “Perennials are the future. Farming in a manner that is resilient—and by that I mean in a way that can adjust to wildly different years—is important for us. A perennial crop like Kernza can do just that.”

The Kernza perennial grain for our pasta is grown on certified organic farms where soil health is prioritized. Unlike annual wheat, the plants produce harvests for two to three years, sometimes longer. After harvest, growers often leave the stalks in the field for grazing animals like cattle, who fertilize the soil naturally as they move over the landscape.

Freshly harvested Kernza. The grains are smaller and more slender than wheat grains, but breeding trials continue to narrow the gap. The Land Institute, Salina, Kansas. Photo by Amy Kumler

Enviro: A Perenial Solution

Annual wheat (top) extends its roots about 3 feet below the surface of the soil. By comparison, the roots of the Kernza plant stretch more than double that length—up to 12 feet—and form a dense, wide tangle that houses billions of beneficial microbes. Photo by The Land Institute.

By growing Kernza®, our farm partners can help rebuild depleted topsoil, prevent erosion and protect groundwater.

Kernza roots can penetrate up to 12 feet into the earth, where they nourish billions of microbes that help replenish soil organic matter, a major driver of long-term soil health. These roots take up nutrients like nitrogen, which can poison aquatic life when allowed to run off into local watersheds. Those massive roots also hold precious topsoil in place, protecting it from erosion by wind and rain.

Annual grains like wheat, rice and corn require tilling and replanting every year with farm equipment powered by fossil fuels. A perennial, Kernza stays rooted in place for at least a few years, minimizing tilling and replanting—and the use of fossil fuels.

Photo by Amy Kumler

History: Ancient Roots

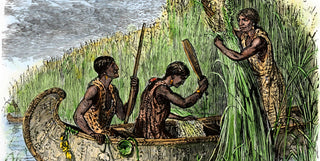

Woodcut of women gathering wild rice from a birch-bark canoe. Wild rice has been a staple grain for the Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes region for centuries. Photo North Wind Picture Archive / Alamy

Kernza® is proof that the seeds of a better future might just lie in the past.

For much of human history, people depended on perennial plants for sustenance. Nuts, seeds, and fruit were staples of many early communities, and people used restorative agricultural techniques like fire-stick farming and forest gardening. But starting about 10,000 years ago, humans became increasingly dependent on annual crops like maize and rice. These crops helped drive population booms, which in turn pressured early farmers to increase their yields. In the 20th century, fossil fuels facilitated an unprecedented increase in annual food crop production—but it came at the expense of soil health. With each harvest, farmers were removing nutrients from their soil faster than those nutrients could naturally accumulate. Today, the earth’s breadbaskets can’t keep up with demand unless synthetic fertilizers come into play. Kernza is proving that an old idea—growing perennials with restorative agricultural practices—can deliver a more sustainable future.

Sprouting the seeds of a better future: At The Land Institute, in Salina, Kansas, decades of breeding trials have turned perennial wheatgrass into a viable grain crop, trademarked as Kernza®. Photo by Amy Kumler

Partners: Guided by Science

Behind the sign for The Land Institute stretches a swath of original untilled prairie, with wild perennial grasses and flowers interwined. This kind of naturally occuring perennial polyculture nourishes the soil; annual monocultures (which make up most of modern farming) deplete it. Salina, Kansas. Photo by Amy Kumler

To develop Kernza, The Land Institute followed nature’s lead.

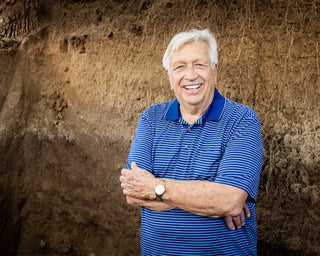

When Wes Jackson looks at the native prairie habitat, he sees an ecosystem working in harmony to increase the fertility of the landscape. When he looks at a conventional wheat field, he sees a one-sided system of extraction that results in ecological destruction.

Nearly 60 years ago, Jackson co-founded The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas, hoping to bring the lessons of the prairie to the production of food crops. As he puts it, “We need wilderness as a standard against which to judge our agricultural practices.”

At the heart of the prairie’s success, Jackson realized, is its dependence on perennial crops grown in polycultures (multiple species growing together). Most modern food crops are produced from annuals grown in monocultures (one species growing alone). Jackson asked, Was it possible to combine the ecological benefits of wild plants with the high yields of cultivated crops?

Countless awards—including a MacArthur Fellowship—later, Wes Jackson and The Land Institute have unlocked what might just be the most revolutionary agricultural advancement in the last 10,000 years. Kernza is more than a delicious grain; it’s helping ignite a global movement for restorative perennial agriculture.

Wes Jackson, co-founder of The Land Institute, in a pit dug to expose and showcase the long, spreading roots of the Kernza plant. Photo by Amy Kumler