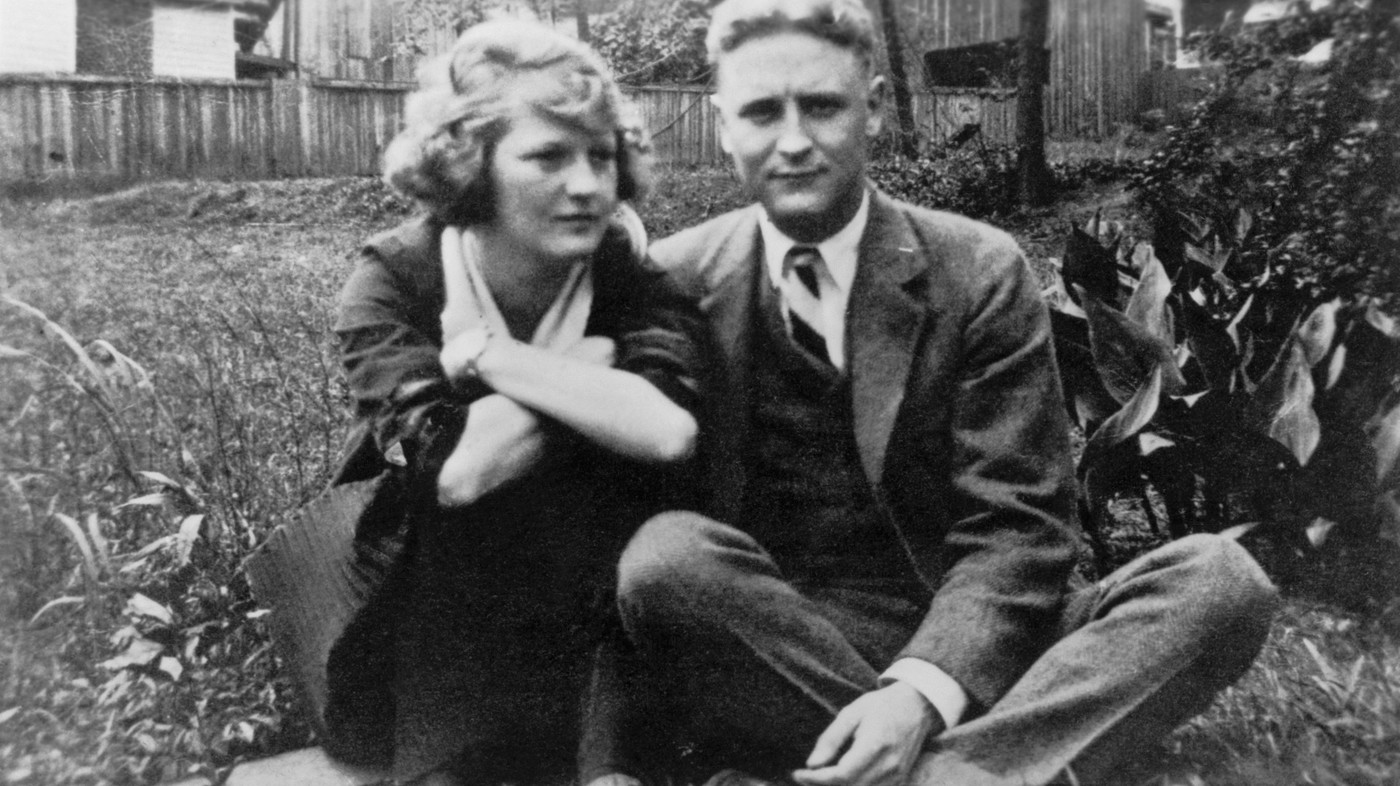

To mention F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald is to invoke the 1920s, the Jazz Age, romance, and outrageous early success, with all its attendant perils. The names Scott and Zelda can summon taxis at dusk, conjure gleaming hotel lobbies and smoky speakeasies, flappers, yellow phaetons, white suits, large tips, expatriates, and nostalgia for the Lost Generation. And even though they are my grandparents, I can’t fail to mention that Scott’s alcoholism and Zelda’s madness are a powerful part of the myth.

My grandparents’ lives are as fascinating to me as their artistic achievements. I’ve always been amazed by their ability to express their love for each other in original and poignant ways. Despite their short and nomadic lives—Scott was born in 1896 and died in 1940, at the age of 44, eight years before Zelda—they left an abundance of correspondence, a window into an extraordinary romance. Their letters reveal two people possessed of an incredible life force and an urge to communicate to the fullest of their powers. Scott’s are astoundingly intimate; they are testimony to his frankness, his caring, his extraordinary ear, and his virtuosity with the English language. Zelda’s are poetic, full of metaphor and descriptions. How they must have loved to open each other’s envelopes! Sometimes.

I was two months old when my grandmother died in a fire at Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina. Zelda’s last letter to my mother in 1948 said that she longed to meet the baby. For me, that letter has been an important thread to the past, an almost accidental link between the generations; it’s a comfort that my grandmother knew of my existence.

Zelda’s letters abound with metaphor. The sky over a lake closes “like a gray oyster shell.” The mountains cover “their necks in pink tulle like coquettish old ladies.” Her prose is lush and multisensory, as when she reminds Scott of the smells of July by the sea. Occasionally, her persona gets scrambled with that of Daisy Buchanan, who appears in The Great Gatsby as a languid and careless member of the idle rich. But in the novel, please note, Scott saved his scorn for the Buchanans, whose vast resources allowed them to have other people clean up their messes. Scott, too, is often confused with his own creation, the ludicrously rich Jay Gatsby. But the novel is a cautionary tale, in which Gatsby tries to use his ill-gotten wealth to recreate the past. Although Scott frequently wrote about high society, to the end of his days he retained a firm midwestern belief in honesty and hard work, as well as a desperately low bank balance.

These letters reveal how little money kept them afloat. And it’s miraculous how much they accomplished on such a tiny budget. When they had it, they spent it. The need for money motivated Scott to write much of his short fiction. Not until the depths of the Depression, when he was forced to take employment in the Hollywood screenwriting factories, did Scott waver from his true vocation. By the time he died, he had completed four novels, 160 short stories (including many self-described formulaic potboilers, which provided the major part of his sustenance), numerous essays and reviews, and a full-length play, The Vegetable—not to mention the hundreds of letters that consumed much of his creative energy, as well as his unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon.

At critical junctures, when Scott had no money at all, he borrowed from his agent, his editor, and his friends, which forced him into a cycle of writing to eradicate debt and then borrowing to write. In 1923, he reported that he had worked twelve-hour days for five weeks to “rise from abject poverty back into the middle class.”

With instinctive media savvy, the newlyweds set about giving America a fresh image of itself as youthful, fun-loving, free-spending, hardworking, and innovative.My mother, their only child, knew this cycle well. She described Scott’s relationship to money: “He worshipped, despised, was awed by, was ‘crippled by his inability to handle’ (as he put it), threw away, slaved for, and had a lifelong love-hate relationship with, money . . . money and alcohol were the two great adversaries with which he battled all his life.”

Because Scott’s books were on a proscribed list at the time of his death, authorities of the Catholic St. Mary’s Church in Rockville, Maryland, denied him burial in ancestral plots. Instead, he was laid to rest in the nearby Rockville Union Cemetery. Eight years later, when Zelda died, the family decided they should be buried together in a double vault. My mother wrote to her grandmother Sayre just after Zelda’s funeral:

I was so glad you decided she should stay with Daddy, as seeing them buried there together gave the tragedy of their lives a sort of classic unity and it was very touching and reassuring to think of their two high-flying and generous spirits being at peace together at last—Mama was such an extraordinary person that had things continued as perfect and romantic as they began the story of her life would have been more like a fairy-tale than a reality.

The fairy tale began when Scott and Zelda met in 1918, at a country club dance in Montgomery, Alabama. Lt. F. Scott Fitzgerald was among the many soldiers stationed at nearby Fort Sheridan, awaiting orders to fight overseas. Zelda, gifted with beauty, grace, high spirits, and expert skills of flirtation, was one of the most popular belles in the region. Her earliest letters to Scott are distinctly girlish. She sounds awash, agoggle in love. Young women of the South, barely free of their Victorian chaperones, still cultivated an utter femininity, a “pink helplessness,” as Zelda calls it. She also refers merrily to her desire for merged identities, for Scott to define her existence. In taking a man’s name, a woman assumed his whole identity, including his career and his social standing—an abject dependency that today would make both sexes wary. Zelda’s declarations of loneliness, of her “nothingness without him” might be alarming to the modern reader, but they are reflections of the time. The Nineteenth Amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote, was not even ratified until August 1920.

In Montgomery the ratio of soldiers to young women was tipped heavily in favor of the women, and competition was fierce among suitors. Scott’s insecurity about losing the woman who had captured his heart is reflected in her mail. Because his side of the correspondence is underrepresented, I’m taking the liberty of including the poem that opens The Great Gatsby, one that few people know he wrote, because he attributed it to a fictitious poet, Thomas Parke D’Invilliers:

Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too,

Till she cry “Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!”

To win her hand, Scott certainly wore the gold hat and bounced.

The Fitzgeralds arrived in New York for the kickoff of the Roaring Twenties. In the boom years, it seemed, the entire city was having one big party. The ticker tape had barely settled along the Fifth Avenue parade route from welcoming the troops home from World War I when Scott’s first novel, This Side of Paradise, astonished his publishers and sold out of its entire first printing. A week after publication, on April 3, 1920, he and Zelda were married.

23-year-old Scott, an overnight celebrity, told the press that his greatest ambitions were to write the best novel that ever was and to stay in love with his wife forever. With instinctive media savvy, the newlyweds set about giving America a fresh image of itself as youthful, fun-loving, free-spending, hardworking, and innovative. And they weren’t too sophisticated to plunge in the Plaza fountain or to spin to their hearts’ content in the hotel doors. Scott described the excitement of those early days in the East: “New York had all the iridescence of the beginning of the world.” And he recalled (an important and too often overlooked ingredient to this fairy tale) “writing all night and all night again.”

My mother was born on October 26, 1921, and was immediately assigned to the care of a nanny. “Children shouldn’t be a bother,” Zelda explained. On the subject of the domestic arts, when Harper & Brothers asked Zelda to contribute to Favorite Recipes of Famous Women, she wrote:

See if there is any bacon, and if there is ask the cook which pan to fry it in. Then ask if there are any eggs, and if so try and persuade the cook to poach two of them. It is better not to attempt toast, as it burns very easily. Also, in the case of bacon do not turn the fire too high, or you will have to get out of the house for a week. Serve preferably on china plates, though gold or wood will do if handy.

Scott’s second novel, The Beautiful and Damned, was published a few months after my mother’s birth. The Fitzgeralds were still enraptured. Scott inscribed his first edition to Zelda:

For my darling wife, my dearest sweetest

baboo, without whose love and aid

neither this book nor any other

would ever have been possible.

From me, who loves her more

every day, with a heartful of

worship for her lovely self.

Scott

St. Paul, Minn.

Feb 6th 1922

A lock of Zelda’s hair, bound with a blue ribbon, was pressed inside the cover, where it remains to this day. During the early years of their marriage, Zelda seemed content to toss her talents aside and become a reckless and decorative wife, although a jovial strain of competition ran through a review she wrote of The Beautiful and Damned for the New York Tribune:

To begin with, every one must buy this book for the following aesthetic reasons: First, because I know where there is the cutest cloth of gold dress for only $300 in a store on Fortysecond Street, and also if enough people buy it where there is a platinum ring with a complete circlet, and also if loads of people buy it my husband needs a new winter overcoat, although the one he has has done well enough for the last three years. . . .

It seems to me that on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and also scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.

Scott’s use of Zelda’s letters is sometimes cited as evidence of his gross misappropriation of Zelda’s talent. At the time, however, it was generally considered a husband’s job to be a provider, and a wife’s job to tend to amenities. Maybe Zelda wanted to give herself a bit of credit for authorship, but at this point there was no serious rivalry between them. A reporter interviewed Zelda a year and a half after the review appeared. For fun, Scott posed several of the questions:

“What do you want your daughter to do, Mrs. Fitzgerald, when she grows up?” Scott Fitzgerald inquired in his best reportorial manner, “not that you’ll try to make her, of course, but—”

“Not great and serious and melancholy and inhospitable, but rich and happy and artistic. I don’t mean that money means happiness, necessarily. But having things, just things, objects makes a woman happy. The right kind of perfume, the smart pair of shoes. They are great comforts to the feminine soul.”

Later, in France, where my grandparents were immersed in an entirely artistic crowd, Zelda’s ambitions sparked. For three agonizing years, she threw all of her creative energy into ballet. That a married woman would try to establish her own artistic identity was unusual, and the strain of such physical discipline, begun at the late age of 27, is thought to have contributed to Zelda’s exhausted mental state.

Her project inspired their most fierce territorial struggle. At issue was their individual right to use their shared autobiographical material.When she suffered her first breakdown, ten years after the wedding, in 1930, the fairy tale ended. Her first letters from the Prangins Clinic in Switzerland, and Scott’s first letters from Paris, are bitter, blameful reinterpretations of their whole relationship. Very little was understood about the nature of Zelda’s suffering. Treatment for schizophrenia, identified as an illness only 19 years earlier, was in its infancy. No helpful drugs existed, only grim and largely ineffective therapies.

By this time, my grandfather’s alcoholism was also full-blown. It’s no secret that F. Scott Fitzgerald was one of the most famous alcoholics who ever lived. But he was a “high-functioning” alcoholic, which made it even more difficult for him to acknowledge or treat his problem. In 1931, little insight had been gained about the negative effects of alcohol. Alcoholism was not regarded as a disease so much as a shameful weakness of character. The AA program, as millions now know it, wasn’t founded until 1935, and it did not become widespread until several years after Scott’s death.

Although no one knew the cause or cure for either of their maladies, there was much reproach. Mrs. Sayre blamed Scott for drinking too much and for not providing stability for her daughter. Scott blamed Zelda’s mother for spoiling her. He also blamed Zelda for being too preoccupied with ballet, while she blamed him for his drunken carousing. Their confusion is poignant, especially when Zelda begged forgiveness for whatever mysterious part of it was her own fault.

The myth persists that Scott drove Zelda crazy. My mother, who was eight years old when Zelda was first hospitalized, and who visited her mother in various clinics over the next 17 years, wrote to a biographer: “I think I think (short of documentary evidence to the contrary) that if people are not crazy, they get themselves out of crazy situations, so I have never been able to buy the notion that it was my father’s drinking which led her to the sanitarium. Nor do I think she led him to the drinking. I simply don’t know the answer, and of course, that is the conundrum that keeps the legend going. . . .”

In 1932, Zelda, yearning to earn her own way in the world, wrote a novel, Save Me the Waltz. Before showing it to Scott, she rushed it to his agent. Scott was understandably irate. It had taken her only a few months of furious activity to write the book. He had been working on Tender Is the Night for several years, had torn up draft after draft, and had read her various passages from it. Clearly, Zelda anticipated that Scott would not want her to use exactly the same material that he was using in Tender Is the Night—the years they had spent in France and her own mental breakdown.

Her project inspired their most fierce territorial struggle. At issue was their individual right to use their shared autobiographical material. Scott was also furious that Zelda had named a character Amory Blaine, after the protagonist in This Side of Paradise. He was certain, as the bill-payer of the family, that her wholesale borrowing would lead to ridicule from his readers and financial ruin. In the end, Zelda removed the parts of her manuscript that overlapped (or, to Scott’s mind, were directly imitative of) Tender Is the Night.

One admirable thing about my grandparents was their ability to forgive infinitely. In the end, Scott helped Zelda with revisions of her novel. He also arranged publication of various articles she wrote and helped produce her play, Scandalabra, written when she was an outpatient in Baltimore. When Zelda began painting seriously, he arranged an exhibition of her work at a New York gallery.

Perfect strangers have volunteered with straight faces that Zelda had all the talent and Scott simply stole her ideas—an injustice that, of course, drove her crazy!I don’t purport to understand my grandparents better than they did themselves. Nor do I believe in latter-day diagnoses, based only on letters and art. Nonetheless, I’ve been exposed to many amateur diagnoses of my grandmother: bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or simple depression. A therapist at a panel I recently attended took the microphone and proceeded to give definitive diagnostic code numbers for my grandparents’ disorders, apparently comfortable diagnosing both of them on the basis of letters and biographies. Perfect strangers have volunteered with straight faces that Zelda had all the talent and Scott simply stole her ideas—an injustice that, of course, drove her crazy!

Zelda had many periods of lucidity and she was never declared legally insane. Her illness had many phases. When she was well, she wrote lyrical, haunting, loving, and nostalgic prose. When she was ill, she sent terribly convoluted warnings to friends about the Second Coming. The strain on Scott was enormous. He tried to be both father and mother to his daughter, to provide the best possible treatment for his wife, and to keep the family financially afloat. But, as he admitted publicly in The Crack-Up, he now faced his own emotional bankruptcy. The wellspring of his story ideas had dried up. Until he was hired as a scriptwriter by MGM, he faced despair.

A trait of Scott’s, made crystal-clear in these letters, was his tendency to overmanage, and, occasionally, to be downright domineering. My mother felt he would have made a fine headmaster of a school. The summer before she entered Vassar College, he warned her:

You have reached the age when one is of interest to an adult only insofar as one seems to have a future. The mind of a little child is fascinating, for it looks on old things with new eyes—but at about twelve this changes. The adolescent offers nothing, can do nothing, say nothing that the adult cannot do better. . . .

To sum up: What you have done to please me or make me proud is practically negligible since the time you made yourself a good diver at camp (and now you are softer than you have ever been). In your career as a “wild society girl,” vintage of 1925, I’m not interested. I don’t want any of it—it would bore me, like dining with the Ritz Brothers. When I do not feel you are “going somewhere,” your company tends to depress me for the silly waste and triviality involved. On the other hand, when occasionally I see signs of life and intention in you, there is no company in the world I would prefer.

Scott wrote weekly to my mother at college. Rather than send her $50 allowance once a month, he insisted on sending her a check for $13.85 every week, probably as a vehicle for his missives. He told her which courses to take, what extracurricular activities were worthwhile, whom to date, her duties toward Zelda, what to read, and how to wear her hair. He critiqued her behavior, her academic performance, and her choice of roommates. Clearly, he loved Scottie very much and his self-confessed desire to preach now had an outlet.

From California, Scott also wrote to Zelda, loyally, warmly, and sometimes perfunctorily. During the last three years of his life, while working as a scriptwriter in Hollywood and, later, on his fifth novel, he began an affair with the gossip columnist Sheilah Graham. Sheilah gave a healthy structure and domesticity to Scott’s last years, but he never completely relinquished his love for Zelda. “You are the finest, loveliest, tenderest, and most beautiful person I have ever known,” Scott wrote to her after their last trip together in 1939, “but even that is an understatement.”

I believe, as did my mother, that Scott and Zelda stayed in love until the day they died. Perhaps it became an impossible and impractical love—part nostalgia and part hope. Perhaps it was a longing for a reunion of all the best qualities in each other that they had once celebrated, and the happy times they had shared, but it was a bond that united them forever. This collection, at last, allows Scott and Zelda, two magnificent songbirds, to sing their own duet.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda: The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Used with permission of Scribner. Introduction copyright © 2019 by Eleanor Lanahan.