The Heian Period of Japanese history covers 794 to 1185 CE and saw a great flourishing in Japanese culture from literature to paintings. Government and its administration came to be dominated by the Fujiwara clan who eventually were challenged by the Minamoto and Taira clans. The period, named after the capital Heiankyo, closes with the Genpei War in which the Minamoto were victorious and their leader Yoritomo established the Kamakura Shogunate.

From Nara to Heiankyo

During the Nara Period (710-794 CE) the Japanese imperial court was beset by internal conflicts motivated by the aristocracy battling each other for favours and positions and an excessive influence on policy from Buddhist sects whose temples were dotted around the capital. Eventually, the situation resulted in Emperor Kammu (r. 781-806 CE) moving the capital from Nara to (briefly) Nagaokakyo and then to Heiankyo in 794 CE to start afresh and release the government from corruption and Buddhist influence. This marked the beginning of the Heian Period which would last into the 12th century CE.

The new capital, Heiankyo, meaning 'the capital of peace and tranquillity,' was laid out on a regular grid plan. The city had a wide central avenue which dissected the eastern and western quarters. Architecture followed Chinese models with most buildings for public administration having crimson columns supporting green tiled roofs. Private homes were much more modest and had thatch or bark roofs. The aristocracy had palaces with their own carefully landscaped gardens and a large pleasure park was built south of the royal palace (Daidairi). No Buddhist temples were permitted in the central part of the city and artisan quarters developed with workshops for artists, metal workers and potters.

No Heian Period buildings survive today from the capital except the Shishin-den (Audience Hall) which was burnt down but faithfully reconstructed and the Daigoku-den (Hall of State) which suffered a similar fate and was rebuilt on a smaller scale at the Heian Shrine. From the 11th century CE the city's longtime informal name meaning simply 'the capital city' was officially adopted: Kyoto. It would remain the capital of Japan for a thousand years.

Heian Government

Kyoto was the centre of a government which consisted of the emperor, his high ministers, a council of state and eight ministries which, with the help of an extensive bureaucracy, ruled over some 7,000,000 people spread over 68 provinces, each ruled by a regional governor and further divided into eight or nine districts. In wider Japan, the lot of the peasantry was not quite so rosy as the aesthetics-preoccupied nobility at court. The vast majority of Japan's population worked the land, either for themselves or the estates of others, and they were burdened by banditry and excessive taxation. Rebellions such as occurred in Kanto under the leadership of Taira no Masakado between 935 and 940 CE were not uncommon.

The policy of distributing public lands which had been instigated in previous centuries came to an end by the 10th century CE, and the result was that the proportion of land held in private hands gradually increased. By the 12th century CE 50% of land was held in private estates (shoen) and many of these, given special dispensation through favours or due to religious reasons, were exempt from paying tax. This situation would cause a serious dent in the state's finances. Wealthy landowners were able to reclaim new land and develop it, thus increasing their wealth and opening an ever wider gap between the haves and have-nots. There were also practical political repercussions as the large estate owners became more remote from the land they owned, many of them actually residing at court in Heiankyo. This meant that estates were managed by subordinates who sought to increase their own power, and conversely, the nobility and the emperor became more separated from everyday life. Most commoners' contact with the central authority was limited to paying the local tax collector and brushes with the metropolitan police force which not only maintained public order but also tried and sentenced criminals.

Even at court the emperor, although still important and still considered divine, became sidelined by powerful bureaucrats who all came from one family: the Fujiwara clan. Figures such as Michinaga (966-1028 CE) not only dominated policy and government bodies such as the household treasury office (kurando-dokoro) but also managed to marry off their daughters to emperors. Further weakening the royal position was the fact that many emperors took the throne as children and so were governed by a regent (Sessho), usually a representative of the Fujiwara family. When the emperor reached adulthood, he was still advised by a new position, the Kampaku, which ensured the Fujiwara still pulled the political strings of court. To guarantee this situation was perpetuated, new emperors were nominated not by birth but by their sponsors and encouraged or forced to abdicate when in their thirties in favour of a younger successor. For example, Fujiwara Yoshifusa put his seven-year-old grandson on the throne in 858 CE and then became his regent. Many Fujiwara statesmen would act as regent for three or four emperors during their career.

The dominance of the Fujiwara was not total and did not go unchallenged. Emperor Shirakawa (r. 1073-1087 CE) attempted to assert his independence from the Fujiwara by abdicating in 1087 CE and allowing his son Horikawa to reign under his supervision. This strategy of 'retired' emperors, still in effect governing, became known as 'cloistered government' (insei) as the emperor usually remained behind closed doors in a monastery. It added another wheel to the already complex machine of government.

Back in the provinces, new power-brokers were emerging. Left to their own devices and fuelled by blood from the minor nobility produced by the process of dynastic shedding (when an emperor or aristocrat had too many children they were removed from the line of inheritance), two important groups evolved, the Minamoto (aka Genji) and Taira (aka Heike) clans. With their own private armies of samurai, they became important instruments in the hands of rival members of the Fujiwara clan's internal power struggle which broke out in the 1156 CE Hogen Disturbance and the 1160 CE Heiji Disturbance.

The Taira, led by Taira no Kiyomori, eventually swept away all rivals and dominated government for two decades. However, in the Genpei War (1180-1185), the Minamoto returned victorious, and at the war's finale, the Battle of Dannoura, the Taira leader, Tomamori, and the young emperor Antoku committed suicide. The Minamoto clan leader Yoritomo was shortly after given the title of shogun by the emperor and his rule would usher in the Kamakura Period (1185-1333 CE), also known as the Kamakura Shogunate, when Japanese government became dominated by the military.

Heian Religion

In terms of religion, Buddhism continued its dominance, helped by such noted scholar monks as Kukai (774-835 CE) and Saicho (767-822 CE), who founded the Shingon and Tendai Buddhist sects respectively. They brought from their visits to China new ideas, practices, and texts, notably the Lotus Sutra (Hokke-kyo) which contained the new message that there were many different but equally valid ways to enlightenment. There was also Amida (Amitabha), the Buddha of Pure Land Buddhism, who could help his followers on this difficult path.

Buddhism's spread was assisted by government patronage, although, the emperor was wary of undue power amongst the Buddhist clergy and so took to appointing abbots and confining monks to their monasteries. Buddhist sects had become powerful political entities and although monks were forbidden from carrying weapons and killing, they could pay novice monks and mercenaries to do their fighting for them to win power and influence in the mishmash of nobles, landed-estate managers, private and imperial armies, emperor and ex-emperors, pirates, and warring clans that plagued the Heian political landscape.

Confucian and Taoist principles also continued to be influential in the centralised administration, and the old Shinto and animist beliefs continued, as before, to hold sway over the general populace while Shinto temples such as the Ise Grande Shrine remained important places of pilgrimage. All of these faiths were practised side by side, very often by the same individuals, from the emperor to the humblest farmer.

Relations With China

Following a final embassy to the Tang court in 838 CE, there were no longer formal diplomatic relations with China as Japan became somewhat isolationist without any necessity to defend its borders or embark on territorial conquest. However, sporadic trade and cultural exchanges continued with China, as before. Goods imported from China included medicines, worked silk fabrics, ceramics, weapons, armour, and musical instruments, while Japan sent in return pearls, gold dust, amber, raw silk, and gilt lacquerware.

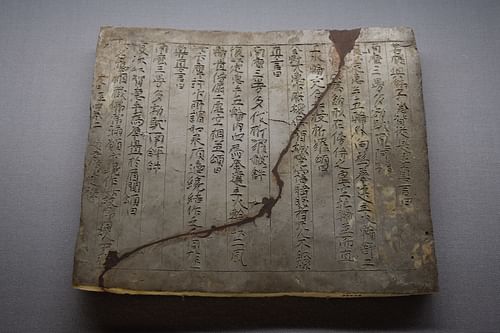

Monks, scholars, musicians, and artists were sent to see what they could learn from the more advanced culture of China and bring back new ideas on anything from painting to medicine. Students also went, many spending several years studying Chinese administrative practices and bringing back their knowledge to the court. Books came too, a catalogue dating to 891 CE lists more than 1,700 Chinese titles made available in Japan which cover history, poetry, court protocols, medicine, laws, and Confucian classics. Still, despite these exchanges, the lack of regular missions between the two states from the 10th century CE meant that the Heian Period overall saw a diminishing in the influence of Chinese culture, which meant that Japanese culture began to find its own unique path of development.

Heian Culture

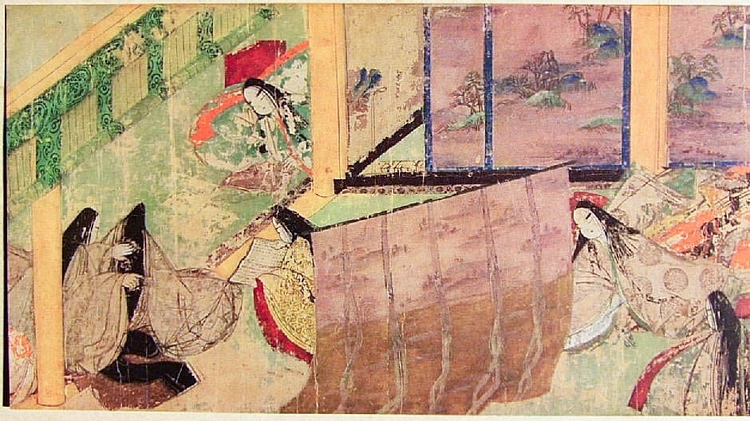

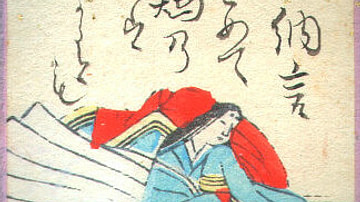

The Heian period is noted for its cultural achievements, at least at the imperial court. These include the creation of a Japanese writing (kana) using Chinese characters, mostly phonetically, which permitted the production of the world's first novel, the Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu (c. 1020 CE), and several noted diaries (nikki) written by court ladies, including The Pillow Book by Sei Shonagon which she completed c. 1002 CE. Other famous works of the period are the Izumi Shikibu Diary, Fujiwara no Michitsuna's Kagero nikki, and a Tale of Flowering Fortunes by Akazome Emon.

This flourishing of women's writing was largely due to the Fujiwara ensuring that their sponsored women at court were surrounded by an interesting and educated entourage in order to attract the affections of the emperor and safeguard their monopoly on state affairs. It also seems that men were not interested in frivolous diaries and commentaries on court life, leaving the field open to women writers who collectively created a new genre of literature which examined the transitory nature of life, encapsulated in the phrase mono no aware (the sadness or pathos of things). Those men who did write history did so anonymously or even pretended to be women such as Ki no Tsurayuki in his travel memoir Tosa nikki.

Men did write poetry, though, and the first anthology of royally commissioned Japanese poems, the Kokinshu ('Collection of the Past and Present') appeared in 905 CE. It was a collection of poems by men and women and was compiled by Ki no Tsurayuki, who famously stated, "The seeds of Japanese poetry lie in the human heart" (Ebrey, 199).

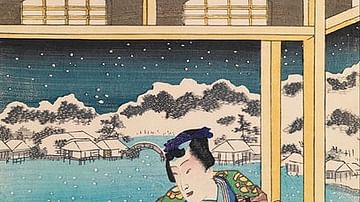

Besides literature, the period also saw the production of especially fine clothing at the royal court, using silk and Chinese brocades. Visual arts were represented by screen paintings, intricate hand scrolls of pictures and text (e-maki), and fine calligraphy. An aristocrat's reputation was built not only on his position at court or in the administration but also his appreciation of these things and his ability to compose his own poetry, play music, dance, master board games like go, and perform feats of archery.

Painters and sculptors continued to use Buddhism as their inspiration to produce wooden sculptures (painted or left natural), paintings of scholars, gilded bronze bells, rock-cut sculptures of Buddha, ornate bronze mirrors, and lacquered cases for sutras which all helped spread the new sects' imagery around Japan. Such was the demand for art that for the first time a class of professional artists arose, the work previously having been created by scholar monks. Painting also became a fashionable pastime for the aristocracy.

Gradually, a more wholly-Japanese approach expanded the range of subject matter in art. A Japanese style, Yamato-e, developed in painting particularly, which distinguished it from Chinese works. It is characterised by more angular lines, the use of brighter colours, and greater decorative details. Lifelike portraits of court personalities such as those by Fujiwara Takanobu, illustrations inspired by Japanese literature, and landscapes became popular, paving the way for the great works to come in the medieval period.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.